Researchers developed a design that allows EV charging within a 10-minute time frame for a typical EV battery.

It is announced in the journal Nature of a combination of a shorter charge time and more energy capacity for a longer range, says Electric Cars Report.

“The need for smaller, faster-charging batteries is greater than ever,” said Chao-Yang Wang, the William E. Diefenderfer Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Penn State and lead author of the study. “There are simply not enough batteries and critical raw materials, especially those produced domestically, to meet anticipated demand.”

As California’s Air Resources Board passed a plan to ban the sale of gasoline-powered cars, the state will retire internal combustion engines by 2035.

”If new car sales are going to shift to battery-powered electric vehicles,” Wang explained, “They’ll need to overcome two major drawbacks: they are too slow to recharge and too large to be efficient and affordable. Instead of taking a few minutes at the gas pump, depending on the battery, some EVs can take all day to recharge.”

Wang, whose lab partnered with the State College-based startup EC Power to develop the technology, also said, “Our fast-charging technology works for most energy-dense batteries and will open a new possibility to downsize electric vehicle batteries from 150 to 50 kWh without causing drivers to feel range anxiety.”

“The smaller, faster-charging batteries will dramatically cut down battery cost and usage of critical raw materials such as cobalt, graphite, and lithium, enabling mass adoption of affordable electric cars.”

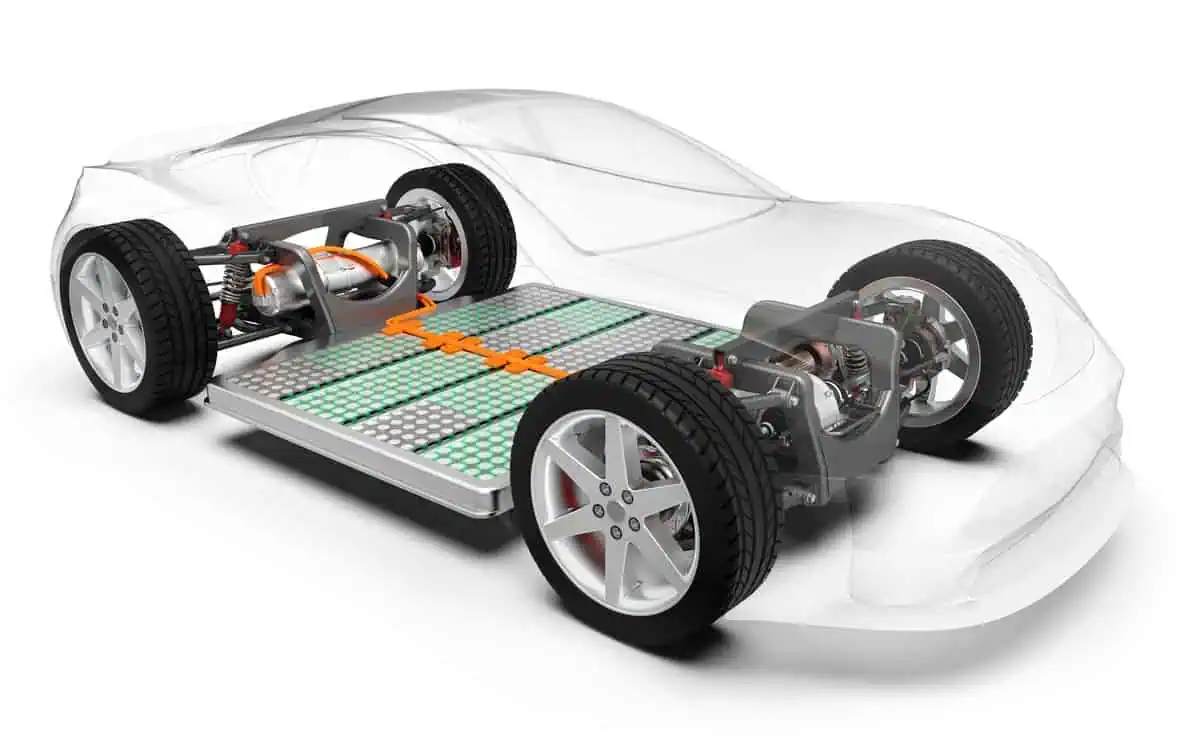

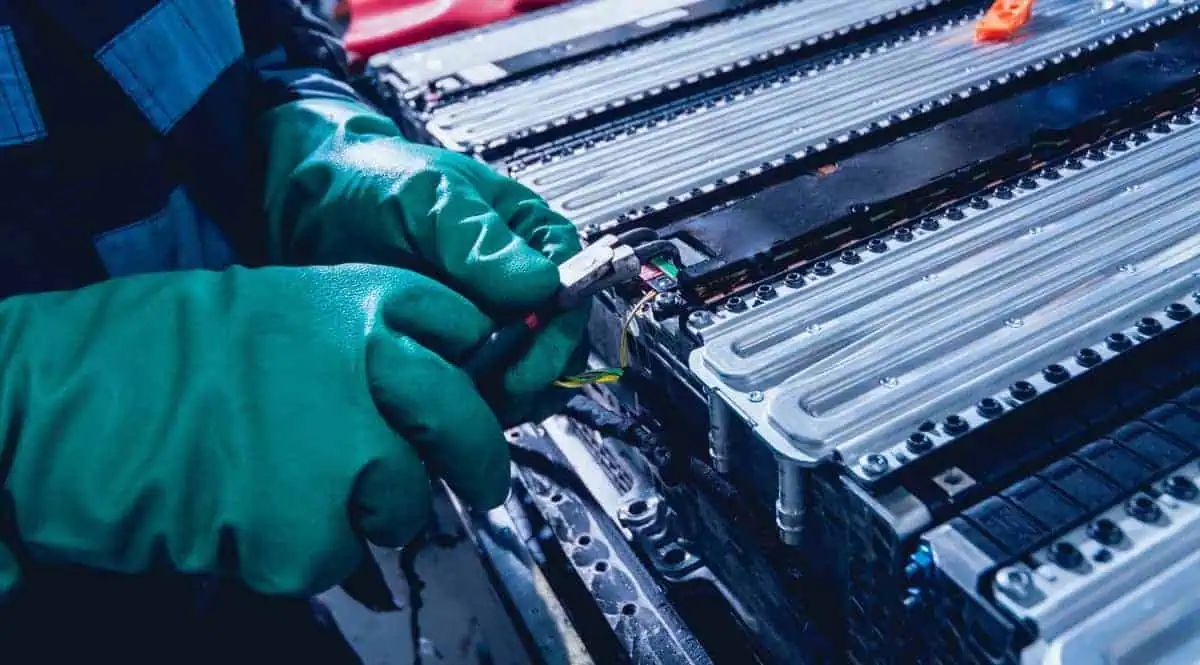

The technology relies on internal thermal modulation, an active method of temperature control to demand the best performance possible from the battery, Wang explained. Batteries operate most efficiently when they are hot, but not too hot. Keeping batteries consistently at just the right temperature has been a significant challenge for battery engineers.

Historically, they have relied on external, bulky heating and cooling systems to regulate battery temperature, which respond slowly and waste a lot of energy, Wang said.

Wang and his team decided to regulate the temperature from inside the battery. The researchers produced a structure that adds an ultrathin nickel foil as the fourth component besides the anode, electrolyte, and cathode. Acting as a stimulus, the nickel foil self-regulates the battery’s temperature and reactivity, allowing for 10-minute fast charging on just about any EV battery, Wang explained.

“True fast-charging batteries would have an immediate impact,” the researchers write. “Since there are not enough raw materials for every internal combustion engine car to be replaced by 150 kWh-equipped EV, fast charging is imperative for EVs to go mainstream.”

The study’s partner, EC Power, is working to manufacture and commercialize the fast-charging battery for an affordable and sustainable future of vehicle electrification, Wang said.

Teng Liu, Xiao-Guang Yang, Shanhai Ge, and Yongjun Leng of Penn State and Nathaniel Stanley, Eric Rountree, and Brian McCarthy of EC Power are the other coauthors of the study.

The work is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Air Force, and the William E. Diefenderfer Endowment.